How a Freeway Interchange Became a Bike Park

/GreenWorks Landscape Architect Matthew Crampton on Linda’s Line at Gateway Green

Each year in East Portland, more than 65 million people whiz right by Portland’s newest urban bike park in cars and trains.

It’s a thin, 25-acre island of trees and meadows that undulates in the center of eleven lanes of traffic, four entrance and exit ramps, the TriMet Red line, Union Pacific freight train tracks, and the I-205 multi-use path. With so much transit happening around it, you’d think the land that’s now known as Gateway Green would be useless.

But visit the park and you’ll immediately realize it’s a treasure. This is because the site was reimagined with the help of a nearly twenty-year effort that began with two community members who saw the opportunity to reuse a piece of the "right-of-way" land to make East Portland better. Interest in the site touched so many different agencies that the Oregon Governor's office got involved to help smooth the way for the project's success.

Gateway Green is a surprisingly nice place to ride off road, and once you get going, noise from the cars and trains just fades into the background. The project is an important step towards providing more space in Portland for people to ride, though more space is still needed. Aside from Gateway Green, the nearest significant off-road riding is more than twenty miles away, at Rocky Point, Stub Stewart State Park or Sandy Ridge.

The park joins a new wave of urban cycling parks like the I-5 Colonnade and Duthie Hill Mountain Bike Parks in Seattle, J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation Bike Park in Boise, Highbridge Park in New York City, and Valmont Bike Park in Boulder. But Gateway Green and the I-5 Colonnade are unique among these examples for their adaptive reuse qualities. Adaptive reuse is when an existing place is redeveloped for a purpose other than which it was originally built or designed for.

Today, heading northbound on I-205, drivers can quickly glance right to view Ted’s Traverse and Linda’s Line, unlikely urban singletrack trails named for the community leaders who got the whole project started. They envisioned a new place for park-deficient East Portland, and an economic driver for the re-imagining of adjacent Gateway District, which if you didn’t know, was started by Fred Meyer in 1954.

But Gateway Green’s fate began even earlier then Fred or Ted Gilbert or Linda Robinson. It began with a volcano.

Rocky Butte, just to the west of Gateway Green, is an extinct cinder cone, the remnants of a volcanic vent and one of nearly thirty like it in the Portland-area. It was Rocky Butte’s location, among other things, that caused the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company to lay down tracks winding around it’s south and east sides around 1879, as Portland’s founders continued to occupy indigenous lands in the area.

As Portland grew, Rocky Butte Jail was built at the base of the butte. The fortress-like structure would stand for nearly 40 years, housing Multnomah County’s male prisoners.

It was the railroad tracks, though, that would turn the area into a major transportation corridor, eventually providing “right-of-way" space for Oregon’s first expressway in 1955, which now forms the east boundary of present-day Gateway Green.

The Banfield freeway, which opened last week…gives one an…idea of what one may expect in rapid travel within this city in the future. Not a single traffic light bars one’s progress on this multi-lane, limited-access, road. Traveling at 55 miles an hour, the drive from 42nd Avenue to Troutdale requires only 12 minutes. (The Oregonian, 5th of October, 1955, via ODOT)

A group of riders climbs the spine up to the highest point at Gateway Green

Throughout the sixties and seventies, Portlanders advocated for alternative transportation options to cars. They organized under groups like the Committee to End Needless Urban Freeways (ENUF) and Sensible Transportation Options for People (STOP). City leaders responded with a network of bike lanes and pathways, and freeway opponents got a major win when they stopped development of the Mt. Hood Freeway.

It was around this time that regional transportation planners were in the thick of designing the Veterans Memorial Highway, or I-205. This highway would most consequentially shape what’s now known as Gateway Green, completely encircling the 25-acres of land with roadways and rail lines that now form the park’s perimeter. Excess dirt and debris from the highway were dumped onto the site, giving it the undulating topography and disturbing the soils.

With attitudes about cars slowly shifting, and spirited opposition to new freeways making headlines, regional leaders agreed, as part of constructing the new highway, to set aside a “right-of-way" corridor for a dedicated busway and embed this project into plans for I-205's construction. Gateway Green provided space for the prospective busses to pass under the freeway and make their way towards Gateway Transit Center, at the park’s south end.

Development of I-205 also meant the Rocky Butte Jail would be demolished. Though the freeway did not pass directly through the fortress-like jail building itself, it passed close enough, and the complex had become out of date—and famous for jailbreaks. It was replaced by a new fortress in downtown Portland.

By the late 1970’s, light rail planning had eclipsed plans for the busway, and its proposed route was given to the new TriMet Red Line extension to the Portland Airport that now runs on the west side of the park.

After that, there was talk of using Gateway Green as a place for TriMet to store unused trains or even as a park-n-ride. Neither happened, and the land at the confluence of two freeways and two railroad lines became just one more mile of “Oregon’s longest lawn” for the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) to mow in the spring.

Gateway Green on a May sunrise

Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, Gateway Green remained 25 nearly inaccessible acres between two semi-directional T interchanges separated by a mile of parallel freeway. It provided what’s known as a “patch habitat” for animals, in conjunction with the much larger, forested slopes of Rocky Butte and the collection of trees lining the streets of the nearby city of Maywood Park. Enterprising local mountain bikers created unofficial trails and inquired at ODOT about turning the place, someday, into a sanctioned mountain bike park.

Agencies struggled to describe what the place actually was. Publications described it as “Excess right-of-way,” “largely vacant,” "the Rocky Butte area along I-205,” and “a highly visible but underused open space surrounded by the confluence of I-84 and I-205...”

An identity for the land began to be realized in the early aughts with headlines like, “Freeway-bound land may become a new Gateway-area park “ as the East PDX News first put Gilbert and Robinson’s idea to readers in a 2008 article.

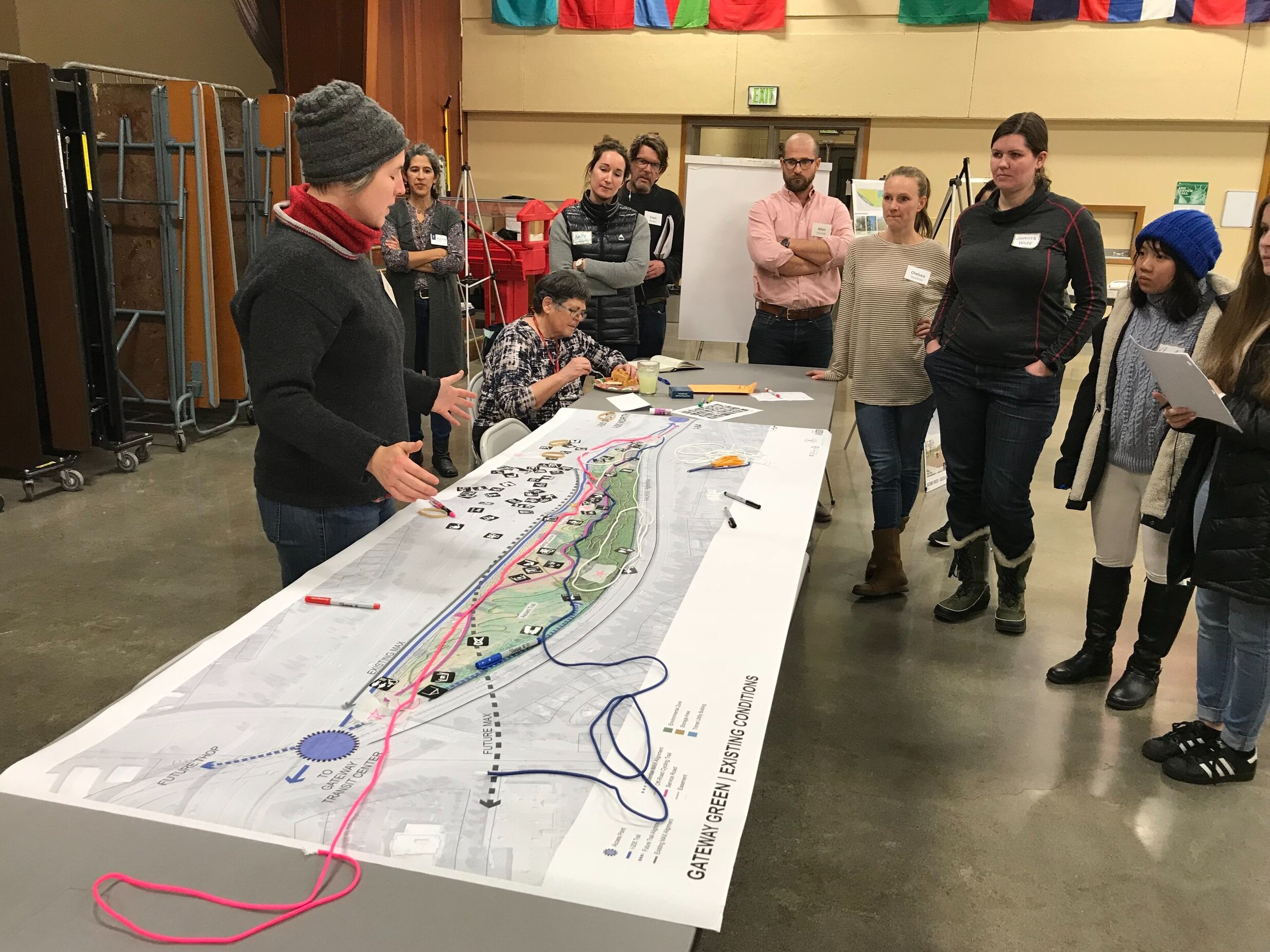

The piece described an excited group of community members, cycling advocates, and planning and design professionals all gathered in the gym at Crossroads Christian Church to dream about what Gateway Green could become. One of the participants in the meetings that day was Gill Williams, now the managing principal of GreenWorks. The meeting was convened by engineering and planning firm David Evans and Associates.

Ted Gilbert and Linda Robinson’s idea had gained steam, a group of supporters, and now permission from the Oregon Department of Transportation (who owned the land) to study potential uses. Efforts built off a giant site analysis done by five Portland State University (PSU) grad students in 2006, and contributed to the 2008 Gateway Green Vision Plan, and the 2009 East Portland Action Plan.

These planning efforts continued, and in 2009 Governor Ted Kulongoski selected the project for inclusion in the Oregon Solutions program, a state-wide community organizing process. The effort raised the profile of the project and resulted in a “declaration of cooperation” that overcame significant barriers to the creation of Gateway Green. Conveners Rex Burkholder, Metro Councilor; and Jay Graves, Owner of The Bike Gallery; gathered stakeholders and committed them to the development of active transportation links at the site and to the development of a park with significant off-road cycling facilities.

One of the major action items from the Oregon Solutions process was the 2010 creation of the Friends of Gateway Green (FOGG). Robinson and Gilbert began the group and since that time it’s been a primary driver of the project and a key partner of Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) in their work developing the site. The group also completed a conceptual design of the park that year.

By 2012, FoGG began serious fundraising by partnering with Oregon’s Kitchen Table, a community fundraising group.

“...in Oregon’s first major civic crowdfunding effort, 756 people contributed to the project, raising nearly $124,000 (toward a goal of $100,000).” - Oregon Solutions

The money was used to hire David Evans and Associates, GreenWorks, and the International Mountain Biking Association to continue design work on the park. As part of this phase, GreenWorks created graphics to help project boosters generate enthusiasm for the project.

“They entrusted us to execute the vision with them.” GreenWorks Landscape Architect and Project Manager for Gateway Green, Ben Johnson said. “We came, we listened, and came up with a design that worked based on what the community had already figured out.” GreenWorks was hired to improve habitat and access to the site, in partnership with PP&R and FoGG.

PP&R completed a feasibility study of the project in 2015. FoGG continued to raise money, compiling another $100,000 from crowdfunding and securing a number of small grants and funding from PP&R by 2016. With nearly ten years of work completed to this point, it was time for an experiment.

In 2017, to test the viability of Gateway Green, PP&R and FoGG directed the first phase of Gateway Green’s development with The Dirt Lab: improved singletrack trails, a bike skills area, and a cement pump track. The Dirt Lab was built by volunteers and staff organized by the Northwest Trail Alliance (NWTA) and the Community Cycling Center. They continue to maintain the park today. “NWTA, in collaboration with the Portland Parks and Recreation and Friends of Gateway Green, worked for 10 years to design and implement the vision for Gateway Green,” the Northwest Trail Alliance says on their website “Each year, more than 150 volunteers contribute over 750 hours of time to build and maintain the trails and bike skills area known as Dirt Lab.”

Dirt Lab was a hit. The new bike specific facilities gained local and national attention and proved Gilbert and Robinson’s idea was wildly popular. This popularity proved people would ride at Gateway Green when given the access. The success led to the continuation of the project and $5.75 million for the next phase of improvements, $1 million as a Nature in Neighborhoods grant from Metro, and $4.75 million from PP&R.

Improvements to the park in phase two included:

Creation of a nature play area

Grading and earthwork to meet ADA regulations and other trail needs

Installation of utilities

Stormwater management

Habitat restoration and plantings

Enhanced off-road bike facilities (constructed by others)

Development of a multi‐use Trail and walking trails

An adaptive cycling course

Creation of an Entry Plaza

Final design for phase 2 at Gateway Green

Phase two was when contributions from GreenWorks made the most impact. Using the discipline of landscape architecture, we worked to balance competing interests in the park with regulations and safety considerations, and to actively listen and act according to the work that had already been done at the park. This listening was done through a series of public meetings where community members were invited to share their thoughts on the future of Gateway Green and, later in the process, review proposed designs.

"One of the things GreenWorks paid particular attention to in the beginning, was the ecology on site,” GreenWorks Landscape Designer Kelly Stoecklein said, “noticing those opportunities where we could create patch habitats and corridors for, in this case it’s mostly animals of flight because of the major highway corridors that are on all sides of Gateway Green.”

“Throughout the process, the crux of the design challenge has been to create a plan that balances active and passive uses along with innovative urban habitat restoration,” Johnson said. A major challenge was fitting “the spine,” the multi-use path through the heart of the park, between the gravity lines, while maintaining suitable grade changes along Gateway Green’s steep south side. GreenWorks principal Gill Williams, Kelly Stoecklein, and Landscape Architect Matthew Crampton also made significant contributions to the project.

Urban Heat island effect context map for gateway green site. Citation: Benjamin Fahy, Emma Brenneman, Heejun Chang, Vivek Shandas, Spatial analysis of urban flooding and extreme heat hazard potential in Portland, OR, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Volume 39, 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212420918310446

Throughout our work, the GreenWorks team paid close attention to research developing on the Urban Heat Island Effect, a consequence of urbanization that occurs, “when cities replace natural land cover with dense concentrations of pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb and retain heat,” according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

The neighborhoods surrounding Gateway Green are some of the most park and greenspace-deficient in the city of Portland. Our design put a focus on preserving and improving forested parts of Gateway Green as well as using aggregate for roads instead of pavement, reducing both the greenhouse gas emissions of constructing the park and decreasing the absorption of heat. The project shows that enhancing underutilized green spaces can play a part in reducing the impacts of climate change, making communities more resilient.

During this design process, the team encountered one of the major problems at the site: How to get water and remove waste. PBS Engineering and Environmental joined the GreenWorks design team and was tasked with solving this problem. The park is encircled by highways, so there aren’t services the construction team could tap into easily. Instead of running pipes under a highway, PBS determined a well could be drilled on-site and a septic field could be constructed to handle the waste.

Finally, in 2020 construction of the long-awaited phase two began according to designs by GreenWorks and our team of consultants: 3J Consulting, Geotechnics, Sentieros Consulting, and Morgan Holen & Associates. Utility and infrastructure improvements were built by Raimore Construction. Trails and jumps on site were designed by Chris Bernhardt and built by volunteers and staff organized by Sasquatch Trails and the Northwest Trail Alliance. Renowned cycling park company Velosolutions was hired to create one of their popular asphalt pump tracks.

An important member of the team that made this park a reality is Portland Parks and Recreation’s Project Manager for Gateway Green, Ross Swanson. Swanson’s leadership of the project made it a reality.

Excitingly, the project incorporated a dedicated adaptive cycling track to provide a place for differently-abled riders to use Gateway Green. The park has an ADA accessible spine, linking riders of all abilities to amenities the entire length of the park, but the gravity lines and skills park are not accessible. The adaptive cycling track, at the north end of the park, was designed with the proper space, slope, sightlines, and obstacles for hand bikes, wheelchair bikes, and trike bikes. The adaptive track at Gateway Green is a small step toward providing more adaptive cycling access to local riders, but it is also the first dedicated adaptive track in Multnomah County.

“Throughout the process, the crux of the design challenge has been to create a plan that balances active and passive uses along with innovative urban habitat restoration.”

The park continues to generate excitement, with nice days absolutely packed. The pump track seems to be especially popular. If you visit early in the morning, you’ll find dedicated cyclists doing rounds of the gravity lines, but you’ll also find folks just hiking through, people watching birds, and children using the nature playground. If you look closely, you’ll usually notice a look of wonder on someone who’s never been there, amazed that something so cool was built at the center of eleven lanes of traffic, four entrance and exit ramps, the TriMet Redline, Union Pacific freight train tracks, and the I-205 multi-use path.

As for the future of Gateway Green, TriMet plans to run a redesigned red line track through the park’s south end, so changes and closures are expected there. A key component of early visions for the park was better connectivity for surrounding neighborhoods. This will require expensive new bridges to be built over the highways and there isn’t a plan to move forward with that at this time. Finally, the prospective Sullivan’s Gulch Trail would link the Eastbank Esplanade to Gateway Green, but there’s no word on when that trail could be up for development.

Gateway Green opened in its current form in December of 2020, during the pandemic winter. Since then, it’s been packed on every nice day. It’s gained regional and national attention for its adaptive reuse of forgotten land, and for the incredible community effort spanning nearly 20 years to make it a reality.

The following groups have been involved in the development of Gateway Green:

Government

City of Portland

City of Maywood Park

Governor’s Economic Revitalization Team

East Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District

Metro

Multnomah County

Oregon Department of Transportation, Region 1

Oregon Solutions

Oregon Parks and Recreation Department

Portland Bureau of Parks and Recreation

Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability

Portland Bureau of Transportation

Portland Mayor’s Office

TriMet

Private

GreenWorks

PBS Engineering & Environmental

3J Consulting

Morgan Holen & Associates

Geotechnics

Environmental Management Systems

C2 Recreation

Sparks + Sullivan

Raimore Construction

Miller Factors

Sasquatch Trails

Chris King Precision Components

David Evans and Associates

SERA Architects

The Bike Gallery

The Lumberyard

Nonprofit Organizations

Friends of Gateway Green

Central Northeast Neighbors

Community Cycling Center

Eastminster Presbyterian Church

International Mountain Biking Association

Mt. Hood Community College

Northwest Trail Alliance

Oregon Sports Authority

Travel Oregon

Did we miss an important detail or get something wrong? Send us an email here to let us know.